By John Haughley via The Epoch Times

The need for data centers to advance 21st-century cloud computing and win the artificial intelligence race with China is such a pressing national issue that Energy Secretary Chris Wright describes it as America’s “next Manhattan Project.”

But estimating how many data centers — a ubiquitous but vague term for “server farms,” supercomputer networks, bitcoin and crypto “mines” — currently exist in the United States is itself an inroad into the quixotic world of cloud computing.

According to Statista, there were 5,426 “reported” data centers in the United States in March.

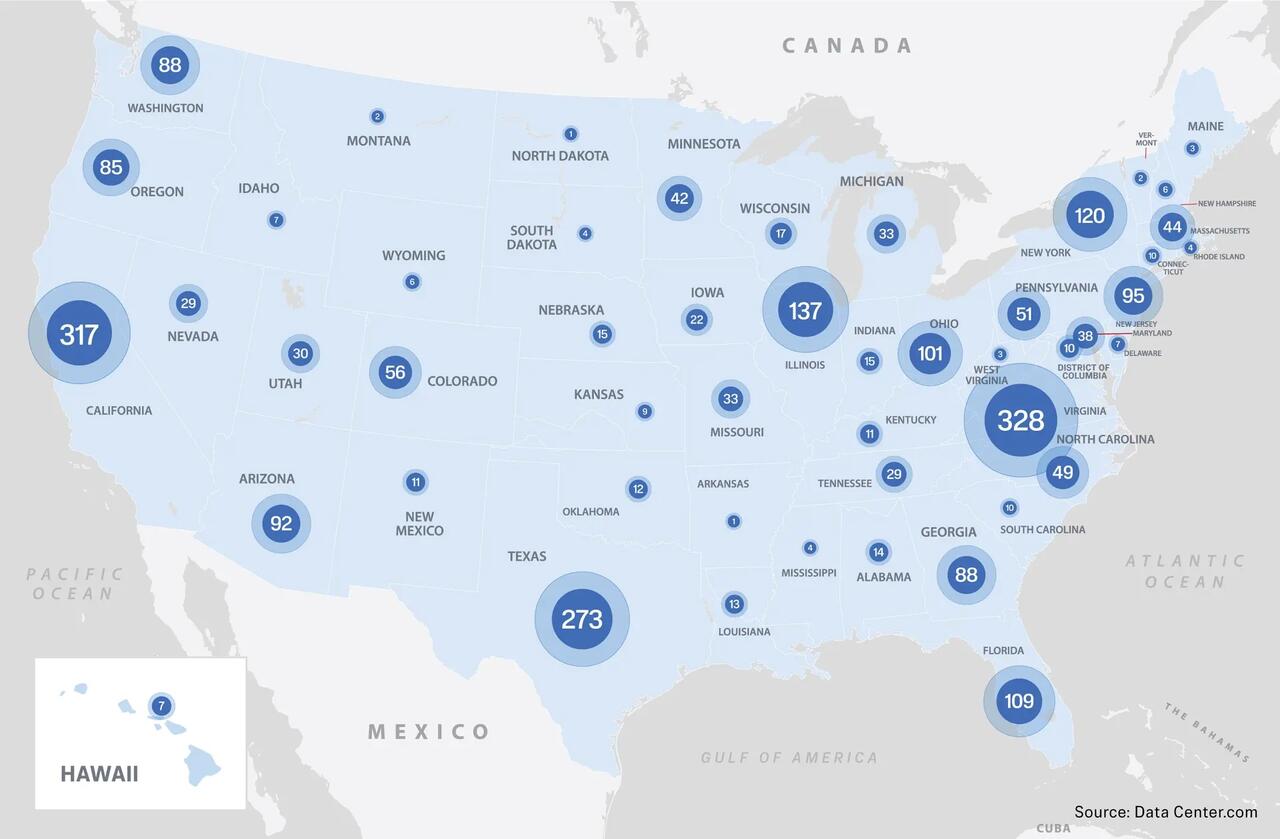

Meanwhile, Denmark-based Data Center Map ApS counts 3,761 listed data centers in the United States. Colorado-headquartered global technology marketplace Data Centers.com says there are now 2,483 centers operating nationwide.

These and other estimates confirm the consensus that the United States has five to ten times more operating data centers than any other country in the world, including China. In fact, according to Visual Capitalist’s rankings, about half of the planet’s data centers are located in the United States.

And yet, as Interior Secretary Doug Burgum said on April 30 at the Hill & Valley Forum, an annual gathering of congressional lawmakers and Silicon Valley venture capitalists, the need to expand the nation’s electrical grid to power more data centers is “one of two existential threats we face as a country”; the other is Iran developing a nuclear weapon. If this need is not met, the country will lose “the AI race with China.”

The Department of Energy estimated last year that the projected energy demand for data centers will triple by 2028. The North American Electric Power Reliability Corporation predicted the same figure a year earlier.

These “load growth” estimates, released after years of relative stagnation in electricity consumption, were released after the advent of OpenAI ChatGPT in late 2022. This shockwave shook utilities, regional transmission operators, and state utility commissions, forcing them to rush to expand power grids to accommodate the projected growth of data centers.

The result was a data center construction boom. In late 2024, Texas-based commercial real estate services firm CBRE projected that more than 4,750 data center projects would begin in the United States in 2025, “almost as many … as already exist” across the country.

According to a September 2024 analysis by Dodge Construction Network, new buildings designed to house data centers will constitute “the fastest growing segment of non-residential construction planning.”

However, there is no unified register documenting how many proposed data centers are currently being reviewed by local planning commissions.

That whim gave rise to Data Center Watch, a research firm that tracks the trend and its opposition, said founder Robert McKenzie, a former associate professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University.

McKenzie told The Epoch Times that much of the media coverage of data centers was “very specific, anecdotal” local news and social media coverage.

“We hadn’t seen anyone collect all the data. So we thought, what if we looked across the country? We weren’t sure what we would find.”

Data Centers.com, a global “technology marketplace” headquartered in Colorado, lists 2,483 data center locations currently operating in the United States. Illustration: The Epoch Times.

McKenzie said that in weekly updates from open-source Google searches, Data Center Watch has been tracking two trends, the first of which is a higher number of data center proposals than initially thought.

Another trend is local opposition, which also helps to track new data center projects. “Lots and lots of publications and bloggers are talking about anecdotal cases… local opposition here and there; there’s more local opposition than we could have imagined,” he said. “In other words, we keep hearing about these projects coming, but they’re already here.”

Additionally, load forecasting is difficult because many data center developers submit multiple proposals but plan to build only a few. At the Association of National Regional Utility Commissions’ winter energy policy conference in February, Angela Navarro, ALN’s president of policy and law, told state public utility commissioners that utilities see data center developers “looking for the best deal.”

Not in my backyard

The rapid expansion of data centers is facing opposition from local residents across the country.

A March report by Data Center Watch mapped the emergence of at least 142 local ad hoc groups in 28 states that “organized to block data center construction and expansion,” with $18 billion worth of planned data centers “blocked” and $46 billion worth “delayed” between March 2023 and March 2025.

McKenzie acknowledged that the report, like Data Center Watch’s weekly updates, is an incomplete summary. It is derived from “public statements or what happens in a public meeting, such as a press release or media coverage,” he said.

An aerial view of an Amazon Web Services data center in Stone Ridge, Virginia, on July 17, 2024. There were 5,426 known data centers in the United States as of March 2025, and the Department of Energy projects that number will triple by 2028. Building data centers to support cloud computing has become a national priority as the use of artificial intelligence has skyrocketed, although the boom faces obstacles such as local opposition and power shortages. Nathan Howard/Getty Images

Still, the tip of the iceberg is emerging, showing that data center proposals are causing anxiety in communities nationwide.

“Honestly, when we were writing [the March report], we were like, ‘Oh my God, $64 billion blocked or delayed?’” he said. “That gives you an idea of how much opposition there is at the local level.”

A February survey of 800 people in “16 key states targeted for AI data center development — where OpenAI and others are exploring expansion” — found that 93 percent of respondents agreed that “leading-edge AI data centers are vital to the United States.”

However, only 35 percent of those surveyed in the survey “would vote yes to building a data center in their hometown” if such a proposal were presented to them.

“There is a clear disconnect between the experiences of local residents and what developers are selling to these communities,” said study author Joe Warnimont.

“It’s not necessarily a matter of opposition to technology in their communities,” he told The Epoch Times.

“Rather, the people in these communities want to maintain control over resources and development, whereas right now that is clearly not the case.”

A report by Data Center Watch, a survey by HostingAdvice.com, and a casual Google search reveal a host of objections. Some are unique to specific locations in specific communities, but most point to common issues such as electricity demand, water needs, noise complaints, and potential decline in nearby property values.

Opponents generally question whether projects create jobs that could be created by other uses. They often claim that developers entice local governments to offer tax breaks and incentives — cloaked in confidentiality agreements. Or they report that state lawmakers prevent local governments from rejecting or modifying proposals.

A construction crew works on the CloudHQ data center in Ashburn, Virginia, on July 17, 2024. As data center construction booms nationwide, state utility commissions are racing to expand power grids to meet growing demand. Nathan Howard/Getty Images

Bipartisan backlash

The backlash against the projects is bipartisan. Locals are not welcoming data center projects despite enthusiasm for artificial intelligence, making data centers the new “not in my backyard” hotbed of anxiety, a report by Data Center Watch concluded.

“Where communities once united against the sprawl of factories, warehouses, or retail, now they are against data centers,” the report states.

“From noise and water use to energy demand and property values, server farms have become a new target in the broader backlash against large-scale development. The landscape of local resistance is changing – and data centers are a direct target.”

“I don’t know if [local opposition] has anything to do with political affiliation. It’s just a question of do I want it in my backyard or not?” Warnimont said.

“This is absolutely crosswalk stuff,” said Kamil Cook, climate and clean energy associate at Public Citizen Texas, about local opposition to data center development in the Lone Star State.

In rural Texas, this means that opponents of data centers are usually bright red Republicans.

“Most of the groups we work with are Republican-leaning people who want to stop this expansion,” he told The Epoch Times. “All of the groups we’ve supported have had very strong ties to their local Republican Party. It’s very local, like … the Republican county chairman.”

Four waves

Jon Hukill, communications director for the Data Center Coalition, said most criticisms of data center projects are standard land-use issues that arise regardless of the specific proposal.

Hukill, a six-year-old, 36-member Washington-based trade association, represents “hyperscalers” — companies like Meta, AWS and Microsoft — and “colocation” companies like Equinix, which own data centers leased to operators.

“I think what you’re seeing is a reflection of the increasing number of states and communities where data centers are developing,” he told The Epoch Times. He noted that these activities are new to the public eye and that many of them are being designed and built in “secondary” and “tertiary” markets, where historically there has been little industrial development.

Hukill said there have been four general waves in the development of data centers, which emerged in the 2000s with the growth of the Internet.

The first wave, he said, was in New York and New Jersey, “because of the proximity to Wall Street – because of the need for very fast transactions.”

The second wave took root in California’s Silicon Valley and Northern Virginia, commonly referred to as “data center alley” and home to the world’s densest concentration of data centers, Hukill said.

The third wave is unfolding in secondary markets, such as suburban or suburban communities in Ohio and Georgia, he said, and increasingly in tertiary markets.

“We’ve actually just seen the development of tier-three markets in the last couple of years where there’s really been very little history of data center development. Think about places like Mississippi, Alabama, Iowa, Indiana,” Hukill said. “That’s where the resistance comes in.”

There are numerous reasons for this development, such as cheaper land, affordable energy, water availability, and local governments wanting economic development.

“There’s a lot more interest in [terminal markets], where you’re starting to see more and more investment — you know, ‘billions of Type B investment’ — in some states where it used to be only in primary markets,” Hukill said. “It’s important to understand that the data center industry is not monolithic.”

Land use attorney Colleen Gillis, founder of Curata Partners in Reston, Virginia, is a veteran of planning and zoning litigation before local governments in Loudoun County and elsewhere in Data Center Alley. She is also a member of the Urban Land Institute’s Data Center Product Council. The organization’s local data center development guidelines address common concerns raised by developers and critics.

An aerial view of data centers near Ashburn, Virginia, on July 17, 2024. Northern Virginia, known as “Data Center Alley,” is home to the world’s largest concentration of data centers. Nathan Howard/Getty Images

“You know,” Gillis told The Epoch Times, “some of the challenges facing data centers are context-specific. Where are they located? What is their visual impact or their compatibility impact?”

“In some jurisdictions where population growth is rapid, traffic is an issue, and school construction or school capacity is an issue,” Gills continued, the criticism is a general anxiety about growth and development, not necessarily specifically about data centers.

Developers have acknowledged that these local challenges are legitimate, he said. “It’s a bit like learning artificial intelligence. Data center companies are getting a better understanding of what they need to do to be good neighbors.”

But Gillis said “misconceptions” persist, including: “If you have a data center in location A, the data center you build in location B is the same – same impacts and same challenges, same water use, same electricity use.”

Point counter Point

The most frequently cited issues with data center projects are the huge electricity and water requirements, the resulting noise, and job creation.

Other issues, such as tax revenue generated by projects, development incentives protected by confidentiality agreements, or state legislators preventing municipal planners from rejecting proposals, are also common among the problems, each deserving of separate analysis.

Electricity

Accelerated data center development will cost consumers in 13 Midwestern states up to $9.4 billion starting this year, according to independent market monitor Monitoring Analytics. Those 65 million customers include 1,100 member companies in the PJM Interconnection regional transmission organization.

According to a December 2024 analysis by the Department of Energy, data centers consume 10 to 50 times more energy per square foot than similarly sized commercial buildings.

Amazon Data Services’ data center campus in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, will eventually consume as much electricity as it takes to power the entire city of Pittsburgh, a senior Amazon executive told the Pennsylvania Capital-Star.

Goldman Sachs Research predicts that global energy demand for data centers will increase by 50 percent by 2027 and by as much as 165 percent by the end of the decade.

And while data centers consumed about 4 percent of the nation’s electricity in 2023, they could account for up to 12 percent of total U.S. electricity consumption by 2028, according to a December 2024 report from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Gillian Graber, executive director of Protect PT, whose nonprofit opposes a proposed data center project in Westmoreland County, said among the concerns of local residents is “the demand that data centers will bring to the grid.”

“Pennsylvania residents may see increased utility costs — electric and gas — as a result,” he told The Epoch Times.

“Electricity availability is a major challenge for the industry, and this applies to the data center industry as well as all 21st century industries,” said Hukill.

“One of the reasons [for grid expansion] is the demand for data center services. Part of that is due to data retrieval and production. It’s the electrification of everything – businesses, electric cars, home appliances. Those are also big loads.”

Many data center developers prefer renewable energy sources like wind, solar and nuclear over natural gas or coal, but they can’t wait for small modular nuclear reactors to become widely available. They’re going where the energy is available, said Aaron Tinjum, vice president of energy policy for the Data Center Coalition, speaking at the Energy Policy Conference in Washington in February.

Many are also trying to “co-locate” to power plant sites, decommissioned coal-fired power plants, or build their own electricity generators that can boost capacity instead of connecting to the grid.

A data center owned by Amazon Web Services (front right) is under construction next to the Susquehanna Nuclear Generating Station in Berwick, Pennsylvania, on Jan. 14, 2024. Ted Shaffrey/AP Photo

“We have customers who have said, ‘You know, it’s taking too long for you to get us electricity. We’re going to figure out self-generation in the meantime [and] whatever we don’t need, we’ll sell back to you,’” Gillis said.

Data centers need baseload power, Loudoun County Supervisor Mike Turner said in his influential June 2024 white paper to local planners, “A Changing Paradigm Strategy.”

He notes that renewable energy is not enough to meet the needs of data centers. “The average data center would need 1,000 acres of solar panels,” he said, noting that a 62-turbine wind farm on Martha’s Vineyard would only provide enough energy to support about a dozen data centers in Loudoun County.

Hukill cited a December 2024 analysis by the Virginia Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, which stated that “data centers currently pay full price for the energy they consume, and current rates appropriately allocate costs to customers responsible for incurring them,” without increasing costs for others.

Water

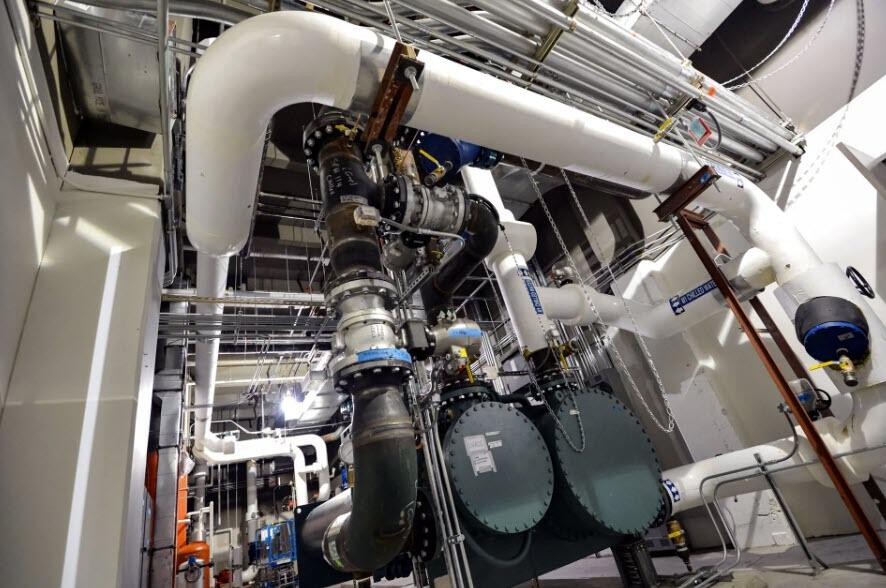

Data centers use a lot of water to cool servers. According to a July 2024 analysis by the University of Tulsa, a single data center can use up to 5 million gallons of water per day. That’s “enough to power thousands of homes or farms.”

Microsoft’s 2022 Sustainability Report showed that water consumption in the company’s data centers increased by 34 percent from 2021 to 2022. According to the Meta 2023 report, data centers used approximately 1.29 billion gallons of water in 2022.

But data center technology is evolving, and few “data centers 2.0 and 3.0” require such water use, with most of them recycling water and using different technologies to cool servers, Gillis said.

“A few years ago, all data centers [used] evaporative cooling. That meant they used a lot of water to cool the data center.” Few do that now, he said.

Citing a report by Virginia’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Hukill said in 2023 that “83 percent of Virginia data centers used the same amount of water – or less – as the average large office building.”

However, in those same tertiary markets where energy is often available and relatively cheap, such as outside Phoenix, Arizona, where dozens of data center campuses were operating in December 2024, water may be scarce.

A Bloomberg News analysis published in May found that two-thirds of data centers built in the United States are located in “extremely water-stressed areas.” Berkeley Lab researcher Arman Shehabi wrote in 2024 that about 20 percent of them “rely on watersheds that are moderately to severely stressed due to drought and other factors.”

Cooling pumps and pipes are seen at Intergate.Manhattan, a data center owned by Sabey Data Center Properties, in Lower Manhattan, New York City, March 20, 2013. The massive water use of data centers is a major concern for planned projects nationwide, along with their high energy consumption, noise and limited job creation. Stan Honda/AFP via Getty Images.

Data center water use can be a factor even in areas with abundant water resources, such as Western Pennsylvania.

“In addition to the usual location, noise, light pollution, and so on, water use is a big issue,” Graber said. “These data centers are going to be powered by gas-fired power plants, and gas-fired power plants need gas, and we already have a huge water use on local resources because of the fracking industry.”

In Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, the Beaver Run Reservoir, a major regional source of drinking water, has been suffering from long periods of drought “for at least two years in a row,” Graber said. At the same time, “fracking companies were still taking our water. So even though Pennsylvanians were being asked to conserve water every day, the fracking industry was still taking it.”

The water used to cool data center servers can be used “for other things, like golf courses.” Eventually, it ends up back in streams and creeks and is processed through the water cycle, Graber said.

However, the water used to fracking gas to fuel data centers “must be directed to injection wells. It cannot be purified enough to be used for human consumption, and so it completely removes water from the groundwater table.”

Noise

Generators, HVAC cooling systems, and power from the electrical grid can produce a hum that is “comparable to the noise of a lawnmower or a busy city street.” According to a study by Sensear, it can cause hearing loss with prolonged exposure at up to 96 decibels.

But again, as the Data Center Knowledge brief points out, noise complaints from nearby residents have prompted adjustments, such as installing mufflers and shock absorbers, to keep noise levels low outside the building.

Data centers are actually “quieter than many common sounds – airplanes, lawnmowers, conversations a meter away,” Hukill said. Data center sound “is not harmful to human hearing and is rarely loud enough to violate noise regulations,” he said, adding, “The vast majority of data centers do not generate noise complaints.”

That claim is documented in a Virginia Legislature analysis, he said. “Now there are sound attenuators. When the community says the cooling equipment on top of a data center is maybe too noisy, data center companies have worked to install sound attenuators to reduce that noise.”

Server banks at the AEP headquarters data center in Columbus, Ohio, on May 20. John Minchillo/AP photo

Job creation

According to Area Development Magazine, building a typical data center creates hundreds of jobs for skilled workers like electricians and engineers. But the long-term on-site employment created by data centers is generally lower than in other industries like manufacturing or corporate headquarters, according to an August 2024 report by Pro Publica.

The report noted that “data centers employ relatively few people on a permanent basis. Server monitoring does not require a large workforce compared to other large industrial facilities, and the facilities are easily distinguished from other giant manufacturing buildings by their small or mostly empty parking lots.”

Warnimont said the relatively low number of jobs — some describe data centers as having “one job for every two occupied acres” — was a recurring criticism in the HostingAdvice.com survey.

“I definitely agree,” he said, noting that many people say, “If it brings a lot of jobs … maybe I’d like it. But if it doesn’t, maybe not.”

However, Hukill said that the lack of jobs created around data centers “is a common misconception,” citing a February report by PriceWaterhouseCoopers . The report found that between 2017 and 2023, “the data center industry supported up to 4.7 million jobs nationwide,” with each direct data center job supporting “more than six jobs elsewhere” in the United States.

“There may be a common perception that the average data center has 50, maybe even 100 full-time employees who have badges,” he said. “But those numbers don’t really reflect the number of jobs that support that data center.”

For example, Hukill said a co-location or “col” data center that rents space to computer network operators, similar to how retail stores operate, adds another layer of employees who manage and maintain the property.

In this situation, in addition to the employees of the company that owns the building, there are also “all the other tenants, technical staff and high-tech workers who keep the servers running,” he said. These workers are “typically not counted” in many employee lists.

Transparency

Objections can vary by proposal and location. But a common argument is that state and local governments offer tax breaks for data center projects, often hidden from public scrutiny by confidentiality agreements that mask proprietary information about the company.

Lack of transparency breeds suspicion and anger, Cook said. “In our experience, one of the biggest problems seems to be that, yes, there is a lack of community engagement.”

He added: “There is no method to inform the community in a way that gives the impression that their voice is valued and that they have a choice in these matters.”