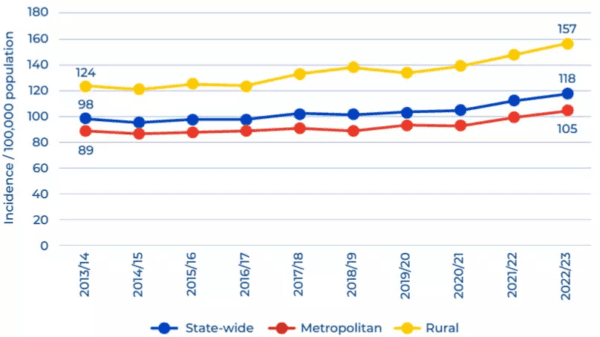

The Australian state of Victoria has recorded an alarming rise in the rate of sudden cardiac arrests and their mortality. In the past five years, the number of people affected has risen by 20 percent, and more than 95 percent are dying.

Latest figures from Victorian Ambulance Cardiac Arrest Registry (VACAR) for 2022/23 show that, of 7,830 people whose hearts stopped beating, only 388 survived.

The news is worse for those living in regional areas, who are 50 percent more likely to suffer an attack than Melburnians and more likely to die as a result.

Regional areas accounted for nearly 2,800 of those incidents, where the rate of cardiac arrests had risen by 15 percent since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The number of sudden cardiac arrests across the whole of Victoria has increased every year since 2018/19, when 6,519 episodes were recorded, and the survival rate has also fallen by almost one percent in that time.

That means “as more incidents occur annually, fewer people are returning home,” explained St John Ambulance Victoria chief executive Gordon Botwright.

“This is absolutely deadly. It’s indiscriminate and it usually occurs without any warning or notice. But the more people that are able to perform CPR, and greater access to public defibrillators can significantly turn around the survival rate,” he said.

CPR-Trained Bystanders Make a Difference

The data also shows that just 10 suburbs accounted for 10 percent of all cases.

| Postcode | Major suburbs | Number of sudden cardiac arrests in the five years to 2023 |

| 3030 | Werribee/Point Cook | 308 |

| 3977 | Cranbourne | 299 |

| 3021 | St Albans | 296 |

| 3199 | Frankston | 288 |

| 3175 | Dandenong | 252 |

| 3350 | Ballarat | 250 |

| 3029 | Hoppers Crossing/Tarneit | 243 |

| 3020 | Sunshine | 229 |

| 3073 | Reservoir | 221 |

| 3174 | Noble Park | 190 |

The VACAR data showed survival rates were heavily influenced by whether or not someone witnessed the cardiac arrest and provided lifesaving care.

One in eight patients who received bystander CPR survived the event, while just one in 20 survived if they had to wait for paramedics.

But if the patient received bystander defibrillation, the survival rate was more than 50 percent.

However, across Victoria, only 30 percent of cardiac arrests were witnessed by a bystander, and the rate was even lower in regional areas. Even if someone saw the event, CPR was given only 64 percent of the time, with that rate also lower in the regions.

St John Ambulance Victoria wants the Victorian government to commit $1.6 million (US$1.04 million) towards its Defib In Your Street initiative, which installs always-accessible defibrillators (AEDs) within 400 metres of every resident and provides free CPR training in postcodes with the highest occurrence of cardiac arrest.

Mr. Botwright said this would allow the program to be extended to the 10 worst-affected suburbs.

Defib In Your Street has already installed 29 AEDs, given CPR training to 1,063 residents in Reservoir, and is halfway to its goal of rolling out 30 units in St Albans.

The next goal is to install a further 30 units and train 5,000 residents in postcode 3020, comprising of Sunshine and Albion.

The effectiveness of readily available defibrillators is backed by research from Latrobe University, which found Defib In Your Street had reduced the average walking time to the nearest unit from 5.87 minutes to 3.55 minutes in Reservoir.

The chance of surviving a sudden loss of heart function declines by 10 percent for every minute without defibrillation.

St John also wants the Victorian government to install AEDs in all public buildings including schools, sporting facilities, jails and theatres, as has been done in South Australia.

“It’s terrible to talk about the cost of a life,” Mr. Botwright said, “but we are talking billions of dollars of impact on the Victorian economy.”

“If just some of that money was passed into programs to help raise community resilience by more CPR and first aid training and more defibrillators, that would be a fantastic outcome for Victorians.”